During the Buddha’s time, like today, other spiritual teachers held myriad views and taught diverse doctrines in contrast to the Buddha’s teaching. Pūraṇa Kassapa, one of the six sectarian teachers, taught that beings are defiled without cause or condition, that they are purified without cause or condition. If such were the case, we could do nothing about the problem of suffering but to stoically resign ourselves to fate. Such a fatalistic doctrine denies the principle of effort, i.e., that a determined effort can be made to improve our inner, mental well-being.

On the other hand, the Buddha’s Teaching, grounded in the principle of cause and effect exemplified in the profound teaching of Dependent Origination, affirms that beings are defiled due to causes and conditions, that they are purified due to causes and conditions. Such being the case, the Buddha reveals that the key to freeing ourselves from all suffering and unhappiness lies in the principle of cause and effect: by uprooting the very causes which give rise to suffering. Thus, to purify the mind it is imperative that we learn about the mechanism by which it is defiled.

Consider the following: we have probably experienced going into a food store to buy a certain item, maybe cheese, curry powder, tea, etc., but when we end up leaving the store, having entered intending to buy only a single item, what has happened? We leave with a bagful of items—some chocolate, a magazine, potato chips, ice cream. How did this happen? We neglected to guard our sense faculties.

While perusing the store in pursuit of our “single item” we saw various forms, e.g., a chocolate bar on the shelf with a pleasing design on the wrapper. When we saw the forms, we became attracted to the pleasant aspect of the object (subha nimitta). Thereafter, we acted out of desire, a defiled mental state, to acquire the object—we placed it in our bag.

To prevent this from happening and to gain control over our mind, we must guard the senses. The Buddha describes how a monk practices sense restraint:

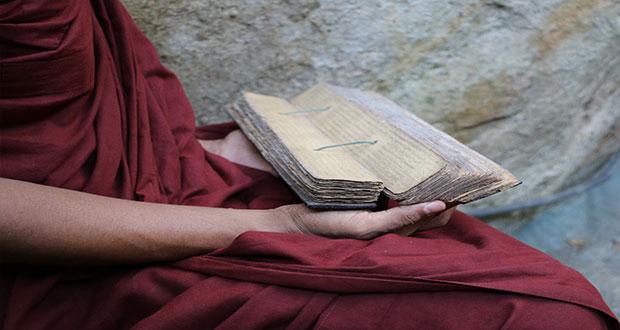

“And how, monks, does a monk guard the doors of the sense faculties? Here, having seen a form with the eye, a monk does not grasp its signs and features. Since, if he left the eye faculty unrestrained, bad unwholesome states of longing and dejection might invade him, he practices restraint over it; he guards the eye faculty, he undertakes the restraint of the eye faculty. Having heard a sound with the ear…Having smelled an odor with the nose…Having tasted a flavor with the tongue…Having felt a tangible object with the body…Having cognized a mental phenomenon with the mind, a monk does not grasp its marks and features. Since, if he left the mind faculty unrestrained, bad unwholesome states of longing and dejection might invade him, he practices restraint over it; he guards the mind faculty, he undertakes the restraint of the mind faculty. It is in this way that a monk guards the doors of the sense faculties.”

AN 3.16 – Apaṇṇaka Sutta

Grasping at the signs of external objects pollutes the mind in the present, wherein states of longing and aversion arise, and moreover one recalls later the agreeable or disagreeable aspect of the objects. In this way, without restraining the sense faculties, unwholesome states arise in the present and future. Yet, restraining the sense faculties is not an easy task; there are many obstacles. In the modern era, a new development in human society dramatically altered the nature of business—the rise of the advertising industry. Over the course of the past century, the industry refined its business techniques by using modern psychology to coax consumers into making purchases. Hence, we are now bombarded by billboards and signs, television, radio, and internet ads.

Advertisements employ enticing imagery and sound to provoke desire in consumers. Unattractive sense objects are likewise employed to arouse hatred, as seen in political ad campaigns. For a long time, the public has been exploited and made the puppets of advertisements provocative of defilements. Though we cannot completely avoid contact with provocative sense objects, advertisements or otherwise, what we can do is restrain our senses so that when we inevitably come into contact with them, we can protect our mind and act with mindfulness and wisdom, rather than getting carried away by emotions.

The Buddha further describes how a monk develops sense restraint:

“Here, Kuṇḍaliya, having seen an agreeable form with the eye, a monk does not long for it, or become excited by it, or generate lust for it. His body is steady and his mind is steady, inwardly well composed and well liberated. But having seen a disagreeable form with the eye, he is not dismayed by it, not daunted, not dejected, without ill will. His body is steady and his mind is steady, inwardly well composed and well liberated.

“Further, Kuṇḍaliya, having heard an agreeable sound with the ear … having smelt an agreeable odor with the nose … having tasted an agreeable flavor with the tongue … having felt an agreeable tangible object with the body … having cognized an agreeable mental phenomenon with the mind, a monk does not long for it, or become excited by it, or generate lust for it. But having cognized a disagreeable mental phenomenon with the mind, he is not dismayed by it, not daunted, not dejected, without ill will. His body is steady and his mind is steady, inwardly well composed and well liberated.”

SN 46.6 – Kuṇḍaliya Sutta

When we are trying to purify the mind, it is important to not further pollute it. That is to say, we want to prevent unarisen, unwholesome states from arising. This is the first factor of the fourfold Right Effort (sammā vāyāma) of the Noble Eightfold Path.

“Monks, there are these four strivings. What four? Striving by restraint, striving by abandonment, striving by development, and striving by protection.

“And what, monks, is striving by restraint? Here, having seen a form with the eye, a monk does not grasp its marks and features. Since, if he left the eye faculty unrestrained, bad unwholesome states of longing and dejection might invade him, he practices restraint over it, he guards the eye faculty, he undertakes the restraint of the eye faculty. Having heard a sound with the ear…Having smelled an odor with the nose…Having tasted a taste with the tongue…Having felt a tactile object with the body…Having cognized a mental phenomenon with the mind, a monk does not grasp its marks and features. Since, if he left the mind faculty unrestrained, bad unwholesome states of longing and dejection might invade him, he practices restraint over it, he guards the mind faculty, he undertakes the restraint of the mind faculty. This is called striving by restraint.

AN 4.14 – Saṃvarappadhāna Sutta

So it is clear that restrain of the sense faculties requires effort. The result of sense restraint is purified virtue. The Buddha additionally mentions that a monk “Possessing this noble restraint of the sense faculties, experiences unsullied bliss within himself.” A disciple who has restrained his or her senses prevents the mind from becoming polluted by contact with external sense objects.

To recapitulate, the Buddha has clearly stated that both effort and mindfulness are necessary to develop sense restraint. If we can mindfully guard the doors of the senses during the day while going about our duties, then we can prevent unarisen defilements from arising in the mind. Along with this heightened purity of mind, we also develop virtue and mindfulness. Moreover, when we return home after work, our mind will be less agitated about what happened during the day. As we develop sense restraint, the mind will become less inclined to recall agreeable and disagreeable objects contacted during the day. With this mental purity come peace of mind, calm and happiness.

By a Venerable Thero of Mahamevnawa Buddhist Monastery

Recent Comments